Izumi Shikibu’s Poetry – The Experience of Loss A Thousand Years Back

In conceptualising and thinking about loss, I wondered what texts might accurately reflect the veracity and reality of loss. In truth, it may be hard, somewhat bordering on impossible, to honestly approach loss without some semblance of a bias. How can loss then be so personal yet so relatable? Perhaps this is because it is a lived experience, one that everyone undoubtedly goes through in its different forms and manifestations. But as I was thinking about a universal, experienced-by-all loss, the romantic in me also considered the loss of love, which was expressed succinctly and beautifully in Izumi Shikibu’s poetry.

In my foray into Classical Japanese Literature, I have found a particular belonging to her sentimental work. The themes of love and loss are at the crux of her poetry and diaries, amidst others like longing and suffrage. It was somewhat comforting, at least for me, to see that these issues pervaded even the most courtly of women a thousand years ago.

Who is Izumi Shikibu?

Izumi Shikibu should be a household name amongst the greats for many interested in Classical Japanese Literature. She was among her courtly contemporaries, the famed Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon, and played a part in inspiring the post-classical poetess, the revered Yosano Akiko. Born in the late 900s of Heian Japan, Izumi Shikibu would eventually become a member of the Thirty-six Immortal Women Poets (女房三十六歌仙), a handpicked group of female poets who were exemplars of Japanese poetic ability. Importantly, Shikibu would leave behind a treasure trove of passionate love poetry, marked and influenced notably by her characterisation as a femme fatale and her relations with multiple men in the Heian courts; eminently, her relationships with the courtly princes, Tametaka, and his brother, Atsumichi. Her life would involve scandals and escapades that spawned two other influential works, Okagami and the Eiga Monogatari.

So why, if anything, should her work be intertwined with loss if most of her life had been filled with companionship and love?

The circumstances surrounding courtly relationships in the Heian era were not the same as today. Courtly men were encouraged to pursue polygamous relationships while the courtly women were made immobile in their verandas, often behind screens. Shikibu herself was a maverick, experiencing risque adventures often unattainable by her counterparts. Yet her many adventures also entailed the risk of loss, especially when Shikibu herself would get too attached to her lovers.

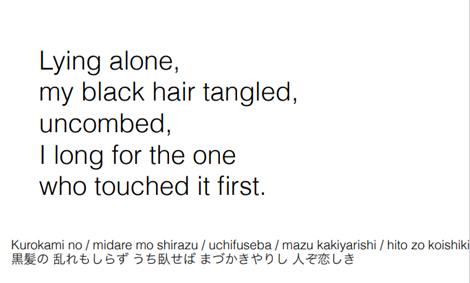

In one of her most famous poems, an older, more mature Shikibu recounts:

I mean – look at the sheer imagery that she provides her readers. Women’s hair had been an object of attraction, and Izumi’s messy hair is allegorical of a night spent in bed with a lover. Her still tangled black hair indicates anxiety, not only for it to be touched and held again, but also a physical analogy for how lost she feels. Izumi yearns to be together, to be taken care of, by her first companion. She is trying to tell the readers that this loss has rendered her incapable of moving on. She lies alone, steeped in a sadness that leaves her immobile in her bed, left to pine and yearn. Is this not anything but relatable? The longing for a lost love, a novel experience, and the urge to be held. She transports her readers back into a foreign yet relatable experience, almost as if the reader themselves could have been there too. It is a heartfelt expression of the loss of something, whatever it may be. We can only assume that she misses, perhaps, her first lover, who we come to find to be unidentified. Regardless, her poetry is not only represented in something that is lost forever, but I find optimism in that her loss may only be temporary.

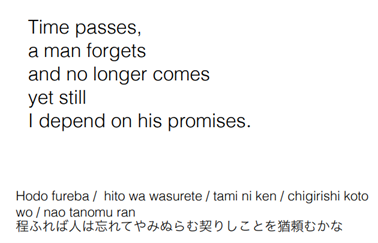

We see her eventual transition from mourning to a zen, an understanding of all things impermanent. Suddenly, her woes of loss are incomparable to the beauty of the abounding life that surrounds her. It is motivational and inspiring that even a poetess who had initially drowned herself in sentimentality and melancholy can eventually come to understand and relook at a loss.

In so doing, re-reading or reinterpreting Izumi Shikibu’s poetry as a monumental instrument for perceiving loss in another light might be a key takeaway. Her intense expressions of losing vis-à-vis poetry demonstrate a key and often overlooked aspect of loss. Where some may find permanence in loss, others might find that loss is but transitionary. It is merely an experience, a phase, or a commonplace of life. Shikibu’s loss tells us that more love may be found eventually. Her ability to lament loss artistically brings comfort and reassurance to readers that though loss pervades all that breathes life, it is not all that life offers.

What can we take away from The Ink Dark Moon?

Though the themes in Shikibu’s poetry connect the reader as it often speaks about the human condition, her colourful presentation of this shared human experience presents and injects alternative understandings of how one may deal and cope with loss. I think it is in the interest of a great writer to attempt to deliver messages that can be somewhat daunting. They could be confrontational, they could be tangential from their original intention, and they could be somewhat controversial. For Izumi Shikibu, she believed that these were all part and parcel of the lived human experience. That loss, like love and permanence, is all on a continuum. So, as we think and ponder about loss, we might be encouraged to listen and be inspired by one of the greatest poetesses of her time. Perhaps with The Ink Dark Moon, one might be encouraged to look at loss, or losses, on a scale that implicates every human emotion and realise that it is just another emotion on the spectrum of lived experiences. I have nothing but high praises for The Ink Dark Moon, and I feel it may be one of the best pieces of poetry I have ever read. It receives only admiration, gratitude, and wonderment from me.

By: Elijah