A Promised Land is a Memoir of Many Firsts

I distinctly remember the day I read about Obama’s win in our local papers, back when I was in Junior College. The historic moment, while far from our shores, could also be felt in my school as we held lively discussions about race, change and hope in our classes. With close to a decade passing since that moment, we now have some length of hindsight to reflect on the legacy of the Obama administration. I have no doubt that the experts – the historians, researchers, and policy think tanks, will be able to give us massive anthologies about Obama’s successes and failures in time to come. What surprised me, however, was how detailed and self-examining A Promised Land turned out to be.

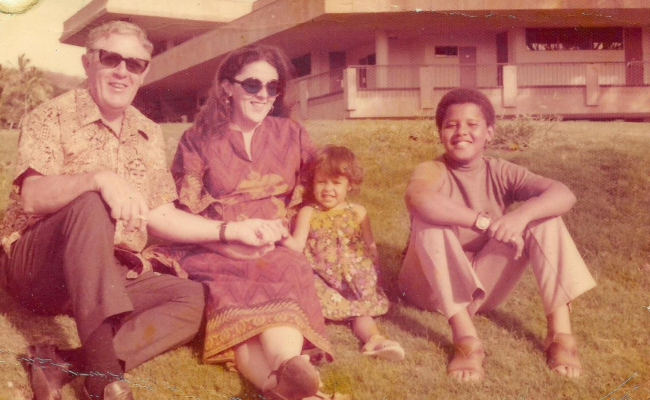

Reading the 768-page tome, I got the sense that Obama was trying to investigate his own legacy. This isn’t just an autobiography that serves to let us in on the secrets of the American presidency. After all, we’ve had countless books before that give us that. Rather, A Promised Land, the first of a two-part series by Obama, takes on a more introspective tone, delivering a comprehensive reflection of the first Black presidency in US history. It is a memoir that tries its best to tell us everything we want to know about Obama – from his personal life growing up in Hawaii and Indonesia, to his views on the universal social, economic and political issues that affect the youth.

The memoir doesn’t disappoint. Right off from the first chapter, you immediately notice the highly distinctive voice of Obama. If you listen to some of his speeches, and then read this book, you will hear that same deliberative, introspective voice in your head as Obama methodologically sorts through his options before every decision — legislative and personal. He does this through both a play-by-play runthrough of the events leading up to his key moments, and through offering deep reflections on the issues that affect not just the United States, but him and his family.

Naturally, therein lies one key appeal of the book. By virtue of making history as the first Black President of a country still scarred by its difficult racial history, Obama (and his family) would have to battle not just allegations of his loyalty to all races and religions, but to minorities in the country who were desperate to see justice, change and hope. He writes emotionally about the pressures of being a minority growing up, and of being seen as “a Black man with a Muslim name who lived in the same neighbourhood as Louis Farrakhan and went to Jeremiah Wright’s church” (page 629). There was anger in the way he had to deal with the birth certificate issue, and sadness in the candid manner he talked about the rise of nativism and white supremacy in his country.

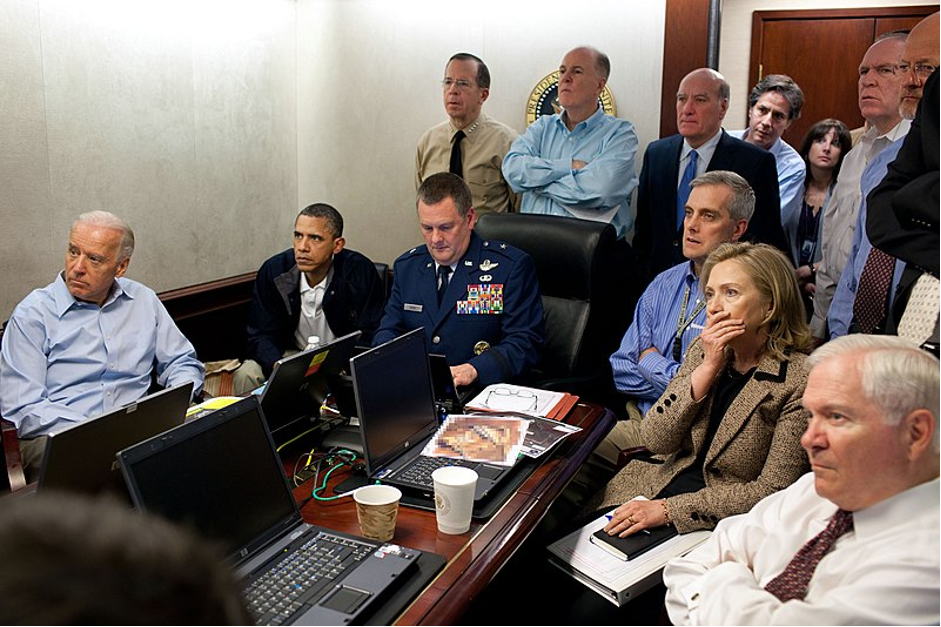

In fact, the intimate way he approaches the biggest issues of the day is what kept me turning the pages of this book. Through an introspective style of writing, he invites readers into areas not typically privy to the public eye, such as the Situation Room (where he oversaw the killing of Osama Bin Laden), the offices of top congress leaders (where he had to fight tooth and nail for his legislative agenda) and into his home above the White House (where he struggles to maintain a semblance of normal family life).

The intimacy of the memoir is also largely driven by the surprising amount of self-critique in the text, particularly after the first quarter. In the aftermath of the killing of Osama Bin Ladin, Obama writes:

“With these thoughts came another: Was that unity of effort, that sense of common purpose, possible only when the goal involved killing a terrorist? The question nagged at me. For all the pride and satisfaction I took in the success of our mission in Abbottabad, the truth was that I hadn’t felt the same exuberance as I had on the night the health care bill passed. I found myself imagining what America might look like if we could rally the country so that our government brought the same level of expertise and determination to educating our children or housing the homeless as it had to getting bin Laden; if we could apply the same persistence and resources to reducing poverty or curbing greenhouse gases or making sure every family had access to decent day care. I knew that even my own staff would dismiss these notions as utopian. And the fact that this was the case, the fact that we could no longer imagine uniting the country around anything other than thwarting attacks and defeating external enemies, I took as a measure of how far my presidency still fell short of what I wanted it to be – and how much work I had left to do” (Page 699).

Sections like these appear frequently throughout the book. It is almost as if Obama was an athlete who, despite all they had accomplished, still regretted that one or two missed opportunities to beat their personal best. He ruminates extensively on the “if only I had”s, “perhaps if I could”s and “maybe if”s, while at the same time defending his major legislative policies and missteps. This is a memoir that simultaneously tries to be honest about the journey of the president, and protective about the legacy that Obama wants to leave behind.

It is perhaps for that reason – of needing to explain, describe, defend, and ruminate, that the book took far longer to write than Obama had originally envisioned. He had wanted to write only a 500-page memoir, and ended up publishing more than 700 pages, with a second part coming. While the length of the work itself was not an issue, I personally felt that the style adopted to deliver the memoir could sometimes appear to be too structured, and slightly overly descriptive. There are deep segues into the details of political processes and routines (such as during his summits at the UN), followed by lengthy ruminations about the pros and cons of particular decisions. For most of the chapters, you will see Obama ending off with a zinger, which, while zesty at first, becomes tired and predictable towards the end of the book.

Nevertheless, Obama’s book delivers on an exceptionally intimate level, delving deep into very universal themes like equality, access, climate change, and resilience. Incredibly moving yet rational in its discussion of major political themes, you will certainly be impressed by Obama’s command of the language, even if it does remind you a little of that time when your dad couldn’t stop talking.

Overall Rating: 4/5

By: Haris Arman Thong

Assistant Director, Publicity, ReadNUS