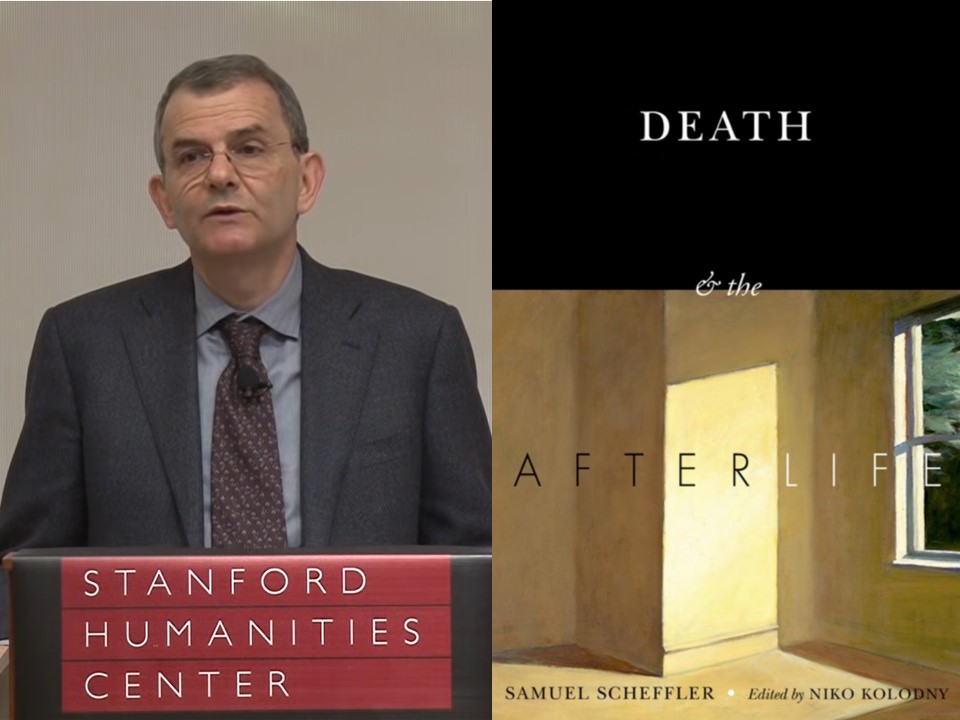

A Review of Samuel Scheffler’s Death and the Afterlife

Do not go gentle into that good night

-Dylan Thomas

Social and Political Philosopher Samuel Scheffler opens up a new area of inquiry with his 2012 book Death and the Afterlife. How would you feel if 30 days after you die, the whole of humanity is extinguished from existence in the world? Would you feel sad or dreadful? Would current scientific endeavours be halted? Would researchers still be as avid to find a cure for cancer as before? Scheffler answers in the negative, claiming that the absence of an afterlife, defined as the continuation of a collective human existence, would put a stop to the meaning in our lives and possibly cause us to land in a minefield of intense ennui.

To be clear, Scheffler is not harping on any theological or mystical element of the afterlife (although he does dwell on them a little bit in the book). He distinguishes between a collective afterlife (as defined above) and a personal afterlife. The latter is the one that is most familiar to most people and is the referent meaning that most people associate with i.e. the proverbial life after death. This differentiation allows Scheffler to highlight his point that a collective afterlife matters to us more than we think. People with a deep-seated notion of a personal afterlife would find the absence of a collective afterlife bearable given that they know that they would continue to exist even after they die and the rest of humanity dies. What this then implies is that the notion of a collective afterlife therefore matters to most people as it is through them that we realise the importance of our present daily endeavours. Scheffler proceeds to make a point or two about the limits of our egoism or individualism.

The book is fascinating in its brevity of expression and depth of intellectual expansion. It is based on the Tanner’s Lecture that Scheffler gave at UC Berkeley and invites commentaries by other contemporary philosophers such as the editor of the book, Niko Kolodny, Harry Frankfurt (Frankfurt rebuts Scheffler’s points about egoism and individualism, arguing that we do not actually care about everyone but only those “who are in some way aware of us”.), Seana Shiffrin, and Susan Wolf. Scheffler provides a very concise formulation of his proposal right from the first part of the book and then proceeds to discuss its implications and objections. In the third part of the book, he diverges to talk about our attitudes towards death.

Going against the claim of irrationality about fear of death, most prominently argued by Greek philosopher Epicurus, Scheffler puts across a firm defence of our ever-present fear of death. Borrowing ideas from Bernard Williams, especially from his Ethics and the limits of Philosophy, Scheffler argues that elements like temporal scarcity makes us fearful of death. The things that we want to do that are nevertheless contingent on our existence more often than not outweighs our “categorical desires” (i.e. desires that do not hang on our existence). For instance, we hope to see our children grow up but to do so would require us to live a relatively long life or at least not to die in their growing-up years. However, things like getting our tooth fixed would not matter when we are already dead – its significance lies in that its portentous decimation does not cause any substantial worry for us.

In essence, Scheffler argues that our lives, along with seeking meaning, is a value-driven one as well. We do not merely want to lead a life, we want a value-laden life and in his opinion, such a life may encompass the idea of a collective afterlife that ensures that whatever we do in this present life does not go to nought eventually. This is an accessible book which attempts to provoke thoughts rather than solve a problem and it does so, as mentioned so far, in a very lucid and engaging manner.

By: Cheong Kwang Aik Eldrick, ReadNUS Events Team member