Behind The Book – Singapore Literature Edition With Yong Shu Hoong

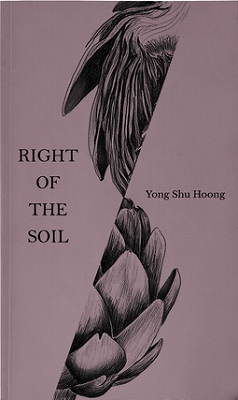

Right of the Soil was shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize 2020.

Yes, the first time I was shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize (SLP) was in 1995, alongside many writers of my generation (including Alvin Pang, Aaron Lee, Daren Shiau and Yeow Kai Chai in the shortlist of 10 poets) who have gone on to publish their first books and then some. Since then, I have been shortlisted for SLP three other times, winning in 2006 for Frottage (2005) and in 2014 for The Viewing Party (2013). Sometimes, I think I’m still in denial.

Tell us more about what prompted you to write some of the poems in Right of the Soil.

Right of the Soil started as a chapbook of 22 poems published by Nanyang Technological University (NTU) and Ethos Books in 2016, after I was writer-in-residence at NTU’s School of Humanities and Social Sciences between 2013 and 2014.

Among the inspirations for the book: SG50, the passing of Mr Lee Kuan Yew, Haw Par Villa. In a way, this book is more Singaporean in its feel than my other poetry collections, with poems addressing topics like belongingness and birthright, the idea of how a person is invariably bound to the land on which he first sets foot. After all, “right of the soil” is translated from the Latin phrase, jus soli, which refers to an unconditional right of a person born within the territory of a country to be conferred citizenship.

I remember, when I was doing my residency in NTU, I was told that its Nanyang Lake (previously known as Nantah Lake) was manually dug by the Nanyang University students in the 1960s. I guess that image of human hands and feet intermingling with soil just got stuck with me.

What are your thoughts on literary awards and prizes?

It’s flattering to be shortlisted and even more affirming to win. I have to say it’s easy to get carried away, so I try to remind myself to stay grounded. Ultimately it is the effort and thought you put into your books, and the luck of assignment as far as the judges are concerned. Perhaps, all the stars need to be somehow aligned. My own policy: deposit the cheque, and then try not to think too much of it when you proceed to write the next book.

Singapore Literature Prize is a prestigious award. How does the award change the reception of one’s work?

To put it crudely, the prize can be summed up in a round sticker your publisher gets to paste onto the cover of your book. Sure, it helps sales – an additional book sold is one more for the tally. And as with most prizes, some readers will be swayed into thinking that the winning book has more worth because of the prize, while others may hold, unwavering, onto their favourite titles that hadn’t won or even been shortlisted. But beyond the initial attention any prize attracts, I hope the readers get to make up their own minds about the book, what the poems mean to them, if those poems speak to them in any way, if at all.

6. Are there any challenges in developing one’s craft when one is trained in a non-arts background? If there are, do you have any suggestions on how to overcome them?

Of course, compared to a person who has gone through a formal literary or arts-based university education, I might come off as someone less aware of certain literary devices or poetic forms. And I’m not as well-read as I’d like to be. But that, in itself, can be an advantage too. So when I first started writing poetry, my poems may feel less clouded by preconceived notions about what poetry should be – save for analysing a few poems (from the Voices anthologies used as textbooks) for Literature in secondary school, reading song lyrics of 1980s electronic bands, and later getting into Beat poetry (courtesy of Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac). So, really, there isn’t any real challenges to overcome.

But over time, one tends to pick things up along the way, anyway. And I’ve also learned to appropriate IT or business jargons to incorporate into my poetry. Another observation: a computer programming language contains structure and syntax – just like the written language that I’ve been trying to shape into poetry.

Thank you for your answers. One final question: why did you agree to this interview?

There’s no good reason to reject this interview request. As a former journalist, I know what it was like to get people to open up and talk. When I’m at the opposite end, I try not to make it difficult for the journalist trying to score an interview.

There’s insufficient avenue, as it is, for a literary work to be made known to the public. So in a way, it’s the responsibility of the writer to help in the promotion and publicity of his books, to repay the publisher’s faith and support.

Also: I’m an NUS alumnus – in Computer Science (class of 1990), almost a different lifetime.

About the author

Yong Shu Hoong has authored six poetry collections, including Frottage (2005) and The Viewing Party (2013), which both won the Singapore Literature Prize, and the latest, Right of the Soil (2018). He is one of the four co-authors of The Adopted: Stories from Angkor (2015) and Lost Bodies: Poems Between Portugal and Home (2016).