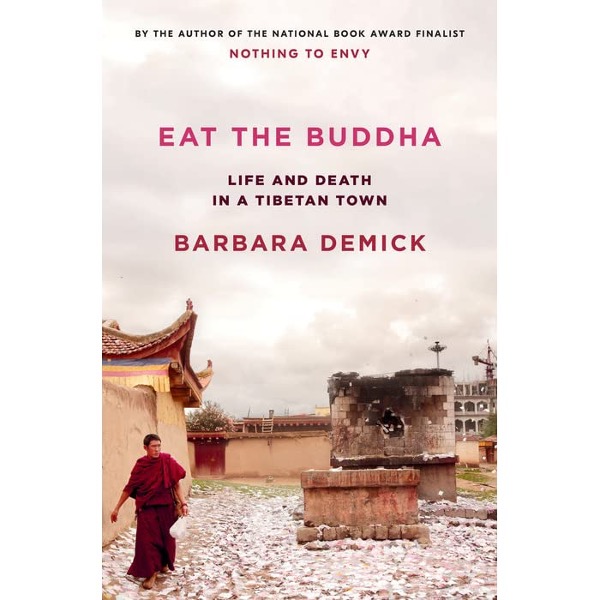

Book Review: Eat the Buddha: Life and Death in a Tibetan Town

In Eat the Buddha, Barbara Demick deftly captures some of the effects brought by Communism and Modernization on a Tibetan town but focuses too much on aspects of traditional culture and religion from a single perspective.

When one mentions the word “Tibet”, three things usually come to mind. The image of pristine untouched grasslands with the Himalayan Mountains as a backdrop, monks in their crimson robes going about their everyday activities and the iconic Potala Palace located on a hillside in Lhasa are images that most outsiders hold of the region. Yet these images belie the fact that the Tibet of today has experienced a tumultuous history of war, political struggle and development, and Barbara Demick incorporates some stories of the past and present inhabitants of Ngaba town in her attempt at capturing the town’s history.

Demick begins her book by telling the story of Tibet’s history prior to the formation of the People’s Republic of China under the leadership of Mao Zedong. Contrary to perceptions that many hold about Tibet, the Dalai Lama was never recognized as the political leader of the Tibetan people outside central Tibet but was more of a spiritual leader to Tibetan Buddhists identifying with the Gelug sect. Tibetans also inhabit areas outside the Tibetan Autonomous Region such as Qinghai and the Western regions of Sichuan Province, where Ngaba town is located. Clashes between rival local chieftains and kings were common and the concept of territory was not as fixed as it is seen today. While Ngaba and Tibet were nominally under the control of the Qing Dynasty with the Qing emperor supervising local politics through officials stationed there and conferring authority on local chiefs through the bestowment of imperial seals, there was much autonomy in day-to-day governance and little change to the traditions and customs that Tibetans practiced in the feudal society they lived in. All this changed when the British invasion of Tibet convinced the Chinese of Tibet’s strategic location, leading to historical events that laid the foundations for tighter Chinese control over Tibet.

In her narration of Ngaba’s history through the lens of its inhabitants, Demick spares no effort in interviewing Tibetan subjects from all social classes in society. She focuses mainly on the period from 1958 onwards, where the Chinese government began to exert stronger control over local inhabitants through collectivization and the elimination of local power structures. We hear of the abrupt detention and downfall of a local chief termed the Mei King in her book who was beloved by his people and co-opted into the Chinese political system, the upending of social class structures as poor peasants took over the property of richer inhabitants and the monasteries, and how political campaigns such as the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution brought widespread destruction to traditional Tibetan culture and suffering of thousands who were killed or imprisoned for being “on the wrong side”. In recent years, fear of growing calls for democratisation and separatism in Tibet have resulted in the supposed suppression of religion and culture due to the Dalai Lama’s association with these areas as a leader of the Gelug Buddhist sect. This has also led to an emphasis on cultivating the people’s loyalty and identification with China through drastic measures, which Demick captures in the book with her stories of several Ngaba residents who migrated to India to enjoy greater “freedom”. Still, she notes the tension that many migrants face as they must choose between staying in China to enjoy better economic prospects or fleeing to India to escape forms of social control such as checkpoints, the supposed restrictions on religion and culture and the inability to obtain passports for overseas travel.

Ultimately, Eat the Buddha proves to be an enthralling read when it comes to describing the experiences of the inhabitants who were interviewed, especially during the early years of the People’s Republic and during the Cultural Revolution. However, the book is marred by occasions where Demick repeats stories told by her interview subjects. She also does not mention much about the lives of other inhabitants in Ngaba such as the Hui Muslim and Han Chinese people, which leaves a gap in the reader’s understanding of the town’s history. Readers are left with a historical account that focuses too much on the distant past and a narrative that neglects the present day-to-day lives of the town’s inhabitants, especially when the Tibetan Autonomous Region close to Ngaba has attained an overall economic growth of 7.8% in 2020. Although this book has been named one of the best books of the year by journalists from acclaimed publications such as The New York Times, and I enjoyed reading her other book on the Yugoslav Wars, it loses some appeal due to its lack of objectivity.

By Bryan Chang

ReadNUS Team Member

Eat The Buddha is available at major bookstores such as Books Kinokuniya, and copies can also be borrowed at NLB Overdrive.