Desserts or Deserters? – The exploration of abandonment in Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s

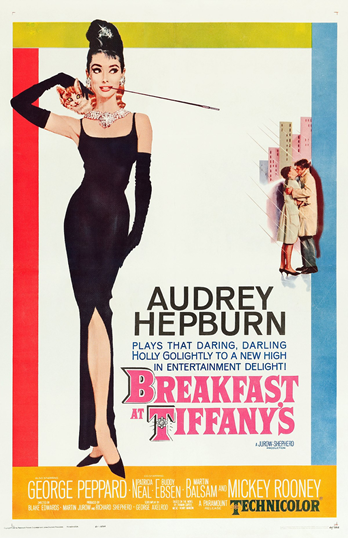

When you think ‘Audrey Hepburn,’ what is the image conjured in your mind’s eye? One would be hard-pressed to not think of her iconic role as Holly Golightly, the lovable socialite in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Clad in a little black dress from Givenchy and her hair in a stylish updo, she continues to be regarded as the epitome of ‘chic’ sixty years on.

Translating text to film

Based on the novella of the same name, the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s draws on many of the dialogue and characters of the book. The basic premise of both mediums are similar — a young male writer moves into the same apartment complex as the vivacious but emotionally fragile Holly, and they grow closer. In the book, the young man in question is the narrator who is hinted to be gay, and their friendship allows readers to learn about Holly’s tragic circumstances. In the film, however, the gay narrator is replaced by a heterosexual male who eventually falls in love with Holly.

In our eyes, Hepburn’s effortless charm and gamine physicality allowed her to play the character perfectly. But this was not the case for the author of the novella, Truman Capote, who had vehemently expressed his displeasure with the casting for the 1961 film. To say that he was partial to Marilyn Monroe playing the role of Holly would be an understatement. As he remarked, “Holly had to have something touching about her…unfinished. Marilyn had that. But Paramount double-crossed me and gave the part to Audrey Hepburn.” Perhaps for Capote, Monroe’s public image as an orphan and a lost girl who was both exploited and saved by the men in her lives would have allowed her to play the alluring but insecure character to a tee.

Capote’s vocal dissatisfaction with numerous aspects of the film adaptation — the cast, the script, and the director — might have its roots in his disdain for film adaptations in general. As he remarked, “The transposition of one art form into another seems to me a corrupt, somewhat vulgar enterprise. […] Why can’t a novel be simply a novel, a poem a poem?”

While I wouldn’t call the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s a “vulgar enterprise,” it is undeniable that the film diverged rather sharply from its source material. Much to the chagrin of readers who love the novella and its sobering treatment of Holly’s insecurities, the film is essentially a formulaic rom-com with a Boy Meets Girl trope. A significant proportion of the film features Hepburn’s Holly Golightly gallivanting around New York with writer and love-interest Paul. These adventures, shot in brilliant Technicolor, set the relatively cheery and optimistic tone of the film. And of course, the film ends just like every rom-com — with a happily-ever-after (as pictured in the movie poster). Much like the book, Holly’s flightiness and fear of being “[stuck] in a cage” serve to be the main conflict of the plot. By having Holly settle down with Paul, the film delivers a satisfying resolution that the novella does not provide.

In contrast, a sense of loss, incompletion, and transience pervades the novella. The story begins with an unnamed narrator and a bartender – two men who Capote alludes to being gay and whose lives have been indelibly changed by Holly. Unlike what her name “Golightly” suggests, her departure dealt a significant blow to their lives as the two men are forced to reckon with the gaping hole that she left in their hearts. Haunted by their concern and platonic love for Holly, the two discuss and speculate on her whereabouts after rumours suggested that she was in Africa. The rest of the story unfolds through a flashback on the part of our narrator as he recounts his interactions with Holly.

This thin book sure packs a punch!

Unlike the film, which is breezy and highly palatable in its own right (save for its use of yellowface), the novella confronts readers with an uncomfortable portrayal of crippling insecurity. This manifests itself in the cycle of abandonment in which Holly actively partakes in. Orphaned at a young age and running away from her cruel foster family, Holly became the child-bride of a Texan vet and a step-mother to his children. In spite of the comfortable life she leads, Holly leaves her husband and step-children for the big city, where she goes from man to man, never committing to one. When she eventually decides to settle down with a diplomat, he soon abandons her after she becomes embroiled in a scandal. And true to the name on her mailbox — “Miss Holiday Golightly, Travelling” — Holly eventually escapes to Africa, leaving behind her pet cat and her friends, the narrator and the bartender.

“Home is where you feel at home. I’m still looking.” – Holly Golightly

Southern roots: the inspiration behind the novella

Capote’s creation of this anti-heroine who is in constant search for belonging can perhaps be attributed to his fraught relationship with his mother. A Southern Belle with great style, Capote’s mother was, according to Capote himself, fragile and eccentric. In his early childhood, his mother had often left him alone in the room when she went out. As he confessed, “That did something to me. I have a terror of being locked in a room — of being abandoned; I have a great fear of being abandoned by some particular friend or lover.” Later, when he was around four, his mother left him to be under the care of her relatives. With the many parallels that can be drawn between Holly and his mother, and between the unnamed narrator and Capote, Breakfast at Tiffany’s can be read as a semi-autobiographical piece. In writing the novella, Capote meditates on his own encounters with abandonment and the universal experience of the search for belonging.

The Verdict?

The film and the book set out to achieve very different ends — the former, a lighthearted rom-com that sweeps viewers off their feet, and the latter, an unflinching look into the sordid world of Holly Golightly — and both succeed in their own way. For me, choosing between the two mediums is a huge undertaking that I shall refrain from doing. However, considering that this is ReadNUS, I must implore you to pick up the novella! At just a hundred pages long (based on the Penguin edition I own), Breakfast at Tiffany’s makes for a short read that gives readers a lot to think about. Capote writes with a deft hand and instantly transports readers to 1940s New York. With an eye for characterisation and dialogue, he writes vividly yet precisely. If you’re looking for a rewarding book to curl up with, look no further than Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

By: Tan Wan Qin

ReadNUS Editorial Member