Psst… Fight Club is Really All About Daddy Issues

Recently, I decided to give Chuck Palahniuk’s infamous Fight Club (1996) a read. As many would know, the novel has become quite the cultural phenomenon – I have heard the line “the first rule about fight club is you don’t talk about fight club” quoted a zillion times and David Fincher’s film adaptation has long been hailed as the archetype of a cult classic. I was thus totally prepared to be attacked by anarchic ideologies and sardonic humour when I sat down to read the novel – and it certainly lived up to its reputation! Fight Club is indeed the pointedly provocative and violent tale that everyone says it is. What caught me off guard, however, was the realisation that daddy issues lay at the heart of the novel. Let me break this down for you.

*warning: spoilers ahead!*

‘A generation of men raised by women’

It is quite apparent that the daddy issues which plague the unnamed narrator in the novel arise from the void left by his absent father. The narrator quips that he ‘knew [his] dad for about six years’ because his father ‘starts a new family in a new town about every six years, such that ‘[it] isn’t so much like a family as it’s like… [setting] up a franchise’ – yet the narrator still moulds his life after his father’s (it was ‘important’ that he went to college because his father did not) and views his father an important figure of authority in his life (he turns to his father for life advice at key stages of his life). However, his father is repeatedly unable to offer him any sound advice and, consequently, the narrator feels like a ‘thirty-year-old boy,’ lost and displaced without the care and guidance of his father. This naturally culminates in the narrator’s pining for a father figure, which (curiously) manifests in his relationship with his boss.

Indeed, the narrator plainly tells us that ‘if you’re male, and you’re Christian and living in America, your father is your model for God. And sometimes you find your father in your career.’ When I read this line, I was actually quite surprised to learn that the narrator views his boss as a father-surrogate because the two are not particularly close – his boss shows concern when the narrator shows up bloody and bruised at work but, on the whole, the narrator does not really regard his boss in a positive light. In fact, I might even venture to suggest that the narrator regards his boss with scorn – after all, he blackmails and intimidates his boss into passivity when his boss questions him about fight club. Perhaps the narrator was enacting a fantasy of being able to dominate the father who abandoned him. In any case, the fact that the narrator self-consciously draws a parallel between his boss and his father makes clear to us that he has a dysfunctional relationship with the father figures in his life.

It is not just the narrator who wrestles with daddy issues in the novel, though. Palahniuk makes clear to us that ‘what you see at fight club is a generation of men raised by women.’ This is another line that took me by surprise. Fight club is, of course, ostensibly a site of sheer masculine energy, replete with violence and comradeship. I had not connected fight club to the domestication of the men in the novel until I read this line and realised that fight club was not simply an outlet for men to vent their frustrations but, further, an avenue for the liberation of the men in the novel. With fight club, the men were no longer ‘slave[s]’ to an (ostensibly and stereotypically feminine) ‘nesting instinct,’ as fight club removed their need to ‘sit in the bathroom with their IKEA furniture catalogue’ and obsess over the décor in their homes to cope with their dissatisfactory lives – lives which they struggled to understand and control on their own. In this sense, then, the men in fight club have been rescued.

Rescued by Tyler Durden, the creator of fight club.

‘Deliver me, Tyler, from being perfect and complete’

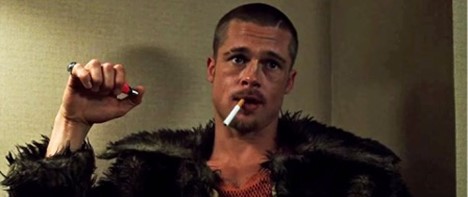

Now, this is the part where I wave my jazz hands: I believe that Tyler Durden represents the ultimate father figure in the novel. What makes Tyler unique is that he is well and truly a man of action. Like the narrator, he recognises that the plight of the oppressed men arises from a lack in the way they had been brought up – unlike the narrator, however, Tyler takes decisive action to ‘put these men in training camp and finish raising them,’ providing them the guidance that they are desperate for through fight club and, later, Project Mayhem. Evidently, he is committed to giving direction to those who suffer from similar psychological issues and offers them a way to regain their self-autonomy vis-à-vis self-destruction. Thus, ‘men look up to him and expect him to change their world.’

When we consider this in light of the revelation that Tyler is an alter-ego which the narrator (consciously or subconsciously) made up, it becomes even more evident that Tyler represents the father that the narrator never had as the narrator conjured Tyler up to cope with and make up for the lack of guidance that he received from his own father. As aforementioned, the narrator’s father is never able to offer the narrator any sound advice. Conversely, Tyler is ‘full of useful information’ and demonstrates self-assured assertiveness as he is consistently able to come up with plans on how to move forward with projects that he undertakes. The narrator thus looks up to Tyler as he is everything that his father is not; he ‘[loves] everything about Tyler Durden, his courage and his smarts.’

More specifically, the narrator admires Tyler’s masculinity as Tyler is able to take command of his life and that, to the narrator, is what it means to be a man. Indeed, the narrator asserts that masculinity is not found in gyms which are ‘crowded with guys trying to look like men’ because ‘being a man [is not about] looking the way a sculptor or an art director says.’ Thus, Tyler Durden is the perfect role model for the narrator as he does not merely present the impression of a man, he is ‘capable and free’ – which means that he is able to create a life for himself that is lived on his own terms.

Moreover, the fact that the narrator stresses that ‘being a man’ is not about striving towards a façade which has been endorsed by a figure of authority also accounts for the advice that his alternate-ego gives him: that he should abandon delusions of grandeur about self-improvement and consider that ‘maybe self-destruction is the answer.’ Before he conjured Tyler up, the narrator had turned to attending support groups for terminally ill individuals as a coping mechanism in his state of loneliness and misery. There, he had listened to how others were grappling with their illnesses and picked up tips on how to regulate himself. His extreme desperation to feel a sense of connection to the people around him as well as to receive some attention and affection is clearly a manifestation of the psychological damage that his father’s abandonment inflicted on him. Yet, after he spends time with Tyler, he no longer attends the support group meetings, trading nourishment for destruction.

As Tyler, the narrator also unknowingly burns down his own house and consistently encourages himself to ‘hit the bottom.’ Additionally, Tyler promotes anarchy in fight club, urging members to disrupt orderly conduct in society. Tyler’s encouragement of destruction and, especially, self-destruction is motivated by a desire to be removed from the trappings of society. His philosophy is: when one is liberated from all the things and people which had once controlled (and thus inhibited) one’s way of life, one becomes liberated as one can finally administer control over one’s own life. From this perspective, self-improvement only makes one comfortable in one’s cage. Such a desire to block out external forces and figures of authority can possibly be traced back to how the narrator’s father had failed in his role as a parent, a key figure of authority that the narrator was supposed to have been able to depend on. Thus, (jazz hands again) Tyler’s advice is rooted in the narrator’s daddy issues as it advances a refutation of external influences and empowers the narrator to eliminate the external forces and figures of authority which govern his life.

‘Everything you ever love will reject you or die’

Alas, in creating Tyler Durden, there is one figure of authority whom the narrator is unable to get rid of: Tyler Durden. Like the narrator’s relationship with his biological father and his boss, the narrator’s relationship with Tyler becomes very complicated by the end of the novel. In fact, a direct parallel can be drawn between Tyler and the narrator’s biological father as both exit his life at some point (‘Tyler’s dumped me… my father dumped me. Oh I could go on and on’) and their disappearance profoundly affects him as he laments that he feels like a ‘Broken Heart.’ Moreover, although the narrator initially idolises Tyler, Tyler eventually also becomes a figure who the narrator comes to harbour animosity towards as Tyler’s power and influence increasingly strip the narrator of his self-autonomy – in his own words, ‘Tyler Durden is a separate personality I’ve created, and now he’s threatening to take over my real life.’ Indeed, the narrator’s relationship with Tyler – and, by association, his attitude towards his father figures – ‘isn’t about love as in caring’ but rather about power, about ‘property as in ownership’ because he has conflated his father figures and masculinity with assertiveness and taking command of his life. It would appear, then, that the narrator’s daddy issues are so severe that his relationship with any person who he regards as a father figure is destined to sour.

Ultimately, I was fascinated by Palahniuk’s exploration of daddy issues in Fight Club because no one had mentioned it to me before I had read the novel. Additionally, I thought it would be worth writing a piece on this as I felt that the many of the narrator’s actions can be traced back to the impact that the absence of his father figure had on his life. Beyond this angle, however, Fight Club also constitutes Palahniuk’s audacious attempt to wrestle with several other ideas, such as a critique of consumer culture and a staggering depiction of dissociative identity order. It is an accessible read, albeit one that contains ideas which may be perceived as problematic or crude. However, if that does not deter you from giving the novel a read, I think you will find that its provocative elements are, well, extremely thought-provoking! Palahniuk’s loud and unhinged ideas are, after all, what Fight Club owes its enduring legacy to.

By Hoh Zheng Feng Sean

Editorial Member