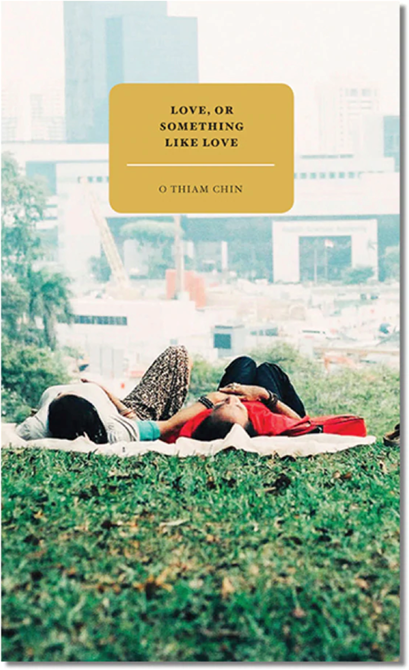

Review of Love, Or Something Like Love by O Thiam Chin

We all define love differently: love is give-and-take, love is compromise, love is lasting and transcendent. Most of all, love is often an indescribable sentiment, perhaps only felt within our hearts and never properly understood. At first glance, O Thiam Chin’s Love, Or Something Like Love seemed to me like a collection of short stories surrounding different types of tender love; I expected to at least be able to characterise these love stories by the Greek Classifications of Love — Eros, Philia, Agape, Storge, Mania, Ludus, Pragma, and Philautia — which already represent a myriad of loves, from lust and romance, to friendship, familial, and self-love. Needless to say, while these eight categories definitely resonate with some of the stories, O turns against any easy categorisation to question what love is, or at least, what something like love is.

All the stories within the collection were enjoyable to varying degrees, but I will review (with spoilers) three in particular that stung me in a different way — these caused me (in a controversial manner) to fold dog ears at the corner of my book pages just to remember the ache as best as I could. In my opinion, these are stories that I would have enjoyed the same even if I had known the ending or resolution; but whether there is even a resolution is another question.

The Verdict

“The Verdict” adopts a confessional tone to trace the relationships involved with offering sexual activity for payment. Though the girl remains the central subject of the entire story, she never truly picks up characteristics of her own — remaining nameless, she “was Linda, Jessie, Yvonne, Madeline, Sarah, Jenny,” whoever they wanted her to be. She was a “projection of their desires,” a “clean slate” and empty canvas for them to imagine a dreamed fantasy, but physically.

Things get complicated when feelings are involved: perhaps some of the customers never felt love under an institutional marriage, searching for these moments of lust just to feel something. But the story ensures this never turns into a romantic relationship. The girl remains but an emotionless, detached entity, voiceless throughout the narrative without reciprocity. In some ways, this makes us question how she, on the other side, feels — whether she, too, fell in love at times, or whether she ever had her preferences (that were ultimately still outweighed by the client’s).

The story also never incites alliance with the speaker: it constantly conjures images of the men’s nuclear family — their wives, their children, their ‘other lives’ — while describing in detail the adultery and affairs. While the story only lasts for three pages, it leaves a strong, stinging feeling that none of this is okay. It makes you wonder, so what if there was love?

And yes, some of the men claimed to truly “love the girl.” Along with how this true love is juxtaposed against their unfulfilling, unsatisfactory marriages and relationships, the complicated, brutal love for the nameless girl seals the story’s sense of tension and difficulty. For all three stories, I will leave you with the final words that, to me, is where O’s writing truly shines.

“…some of us did love the girl, even after what happened later, when all of us were revealed for what we had done. We believed we finally had a chance at love, or something like love. We really did.”

At The Suvarnabhumi Airport

Loving and losing are but different sides of the same coin — to love is to risk the pain and agony of losing. But often, we love because the uncertainty is worth it, or because love itself seems to erase any uncertainty, by comforting and assuring us. The story “At The Suvarnabhumi Airport” shows a pessimistic side of this risk, as a couple visits Bangkok to try to rekindle the spark in their marriage (especially after the husband’s affair). Conversely, they befriend a woman — portrayed as innocently outgoing — who seems to confirm for the wife what she was looking for all along: a signal to walk away. Much like “The Verdict,” “At The Suvarnabhumi Airport” explores the morality and sexual depravity amongst married men.

As the couple, Colin and Kay, befriends the young woman, the narrative portrays their friendship as growing with intimacy: she joins their breakfasts, taking photographs with them, “her arm brushing his,” causing Colin to feel a stir “in the core of his being.” Kay, however, remains rather reticent throughout, at best only remaining neutral about their new friendship; she even terms the trip “just what [they had] wanted,” which, prima facie, readers take to stand for the successful revival of their marriage. Yet, as with how the readers are privy to Colin’s wandering thoughts, she seems to know the ongoings within his mind, ultimately leaving the narrative with an empty ending, and clarifying that what she had “wanted” was not a fixed love with plasters over its cracks, but a motivation to leave and search for a better one:

“When Kay turns to look at him, Colin doesn’t look away. Kay studies his face for a long while, and then she, too, walks away from him.”

Third Eye

Building on the relationship between love and loss, Dr. Katherine Shear — the founding director for the Centre for Complicated Grief at Columbia University — shares how “grief is the form love takes when someone we love dies.” The third story, “Third Eye,” articulates just that. The story follows a man who loses his wife, Susan, in an accident. The man grieves heavily while bringing up his young son, James, who claims to see and hear his mother after the incident.

The story is rather straightforward and direct, but it works in making it sincere and candid. It is interspersed with raw, emotional dialogue between the two characters, punctuated also by silence that is charged with meaning. When they are not having conversations about the elephant in the room (which mainly consisted of James insisting that he saw Susan, and his father wearily begging him to stop mentioning her), the story traces their difficult inner struggles with grieving and adapting to a new life. We all know the five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. While “Third Eye” only resides within the transit from depression to slight acceptance regarding Susan’s death, the other stages (or in this case, feelings) conjure in different ways: the father exhibits denial and anger towards James’s claims about meeting his mother, and the narrative bargains with Susan’s death by having her materialise in James’s world, causing him to nod and smile at her tombstone.

While the story articulates these emotions of grief well, from describing the father’s new struggles with getting James ready for school alone, to how remnants of memories with Susan constantly replay in his head, it leaves some things unsaid, allowing it to carry more weight than anything that can be written in words. When the two characters visit Susan’s tombstone, the entirety of James’s and his mother’s “hidden conversation” is kept secret from the reader, at last only teased when James conveys to his father “Ma says,” followed by ellipsis. Ultimately, readers will never know what Susan says to James, but — perhaps more poignantly than a long conversation would express — we know it leaves them aching, missing, loving, all culminated within the father’s response:

“‘I miss you too,’ I said.”

Love Stories

Maybe the characters in “The Verdict” and “At The Suvarnabhumi Airport” display a selfish, lustful love; we could also argue that the love in “Third Eye” is pragma — an enduring love. I would, however, like to think that O presents these without any intent of classifying them as what we know as love. Maybe these love stories simply depict how we can never truly grasp the complex idea of love and give us a look into the different ways to define — whether morally right or wrong — love, or something like it.

By: Shannon Ling

ReadNUS Editorial Director