Why We Should All Read “Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools”

*Warning: This book contains gruesome details about the tragic mistreatment and abuse of indigenous residential school children. Read at your own discretion.

Walk on, little Charlie

Walk on through the snow.

Heading down the railway line,

Trying to make it home.

Well, he’s made it forty miles,

Six hundred left to go.

It’s a long old lonesome journey,

Shufflin’ through the snow.

– Willie Dunn

In 2022, 215 bodies of Indigenous First Nations children were found buried under the grounds of a British Columbia school–the former Kamloops Indian Residential School–where these children were forcibly taken from their families and assimilated into the ways of the white man. This story no doubt shocked the nation and every other country worldwide, but to the survivors and descendants of these residential schools, and the few who have known about them, it is not a surprising part of North America’s colonised history at all. With the excavation of the bodies of these poor children came the uncovering of a sinister and ugly truth underneath the national and historical rhetoric of Canada and North America as a whole. This ugliness within the historical and social fabric of one of the “nicest countries” in the world encompasses a tragic history of the continued oppression and subjugation of the indigenous people of Canada and the United States.

One of these historical events involves the forcible removal and displacement of indigenous children from their families and homes into residential schools that likely remind one of a haunted penitentiary rather than a safe learning space that a “school” needs to be. The justification for this atrocity appears to revolve around the “un-savaging” of the savage, in which the dominant white governments of Canada and the United States made it their divine mission to educate the savage in the ways of the white man – which includes an effort to deracinate, displace and alienate the indigenous child from their own culture and language. Churchill mentions in his book that the “Indian Department took as its goal “tribal dissolution, to be pursued mainly through the corridors of residential schools”” (Churchill 14).

This is done by enforcing an English-only language rule and instilling cultural practices of the dominant white culture. In essence, the verdict to “Kill the Indian, Save the Man” echoes a sinister attempt to massacre the indigenous individual’s understanding of their own culture, in which their lack of cultural connection leads to a dissolution of their own humanity. This, in turn, tragically leads to their internal self-purging and a manifestation of an internalised trauma that stems from a trauma that cannot be undone.

In the process of alienating and erasing the child’s connection to their culture and language, these children are taken away from their families, repeatedly mistreated and abused by the guardians at residential schools, and isolated within their own country because of the dominant White’s discrimination of the Indigenous people as “lesser than human” and savage.

These children grow up with immense trauma and sorrow from a haunting childhood of physical, mental, and sexual abuse, a loss of family, and a loss of connection to a long and rich culture of the Americas. The Indigenous people of the Americas have a diverse and deep history of civilisation, tradition, culture, spirituality, knowledge and living practices that has influenced the way the world and its civilisations function and operate. For example, traditional Indigenous tribes were extremely adaptable and resourceful in finding ways to live such as their innovative ways of basket weaving, making ceramics and hunting (Benton Museum of Art, “Native American Cultures”). Their proclivity towards spirituality and religious processes in relation to the environment provides a useful framework for modern societies today as we face climate change, because Native American tribes are known to value the resources and landscapes that Mother Nature provides for us, and they were known to inflict little damage on the environment in their various agricultural and hunting practices (Margolin 119).

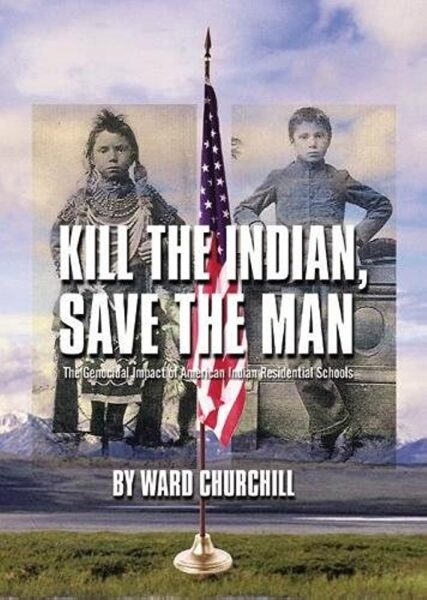

Summarising the pain and intergenerational trauma of the residential children in this article does not even begin to do their stories and lives justice. Ward Churchill’s non-fiction book Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools thus properly spotlights the traumatic impacts of the American Indian residential school, in which he exposes the dehumanising atrocities that have been committed unto the residential school children by the dominant white governments in North America.

He also explicitly reinstates the consequential definition of “genocide” and intentional statewide massacre unto the situation of the residential school children because the legal mobilisation of residential schools throughout North America shows the government’s malicious intent to eradicate the indigenous individual’s semblance of self and culture. The enforcement of residential schooling for Indigenous children also underscores a clear disregard for human rights towards the indigenous children, which also reaffirms the white government’s continuous attempt to further eradicate the indigenous people of North America since the beginning of contact with the Europeans in 1491.

This book serves as an important reminder never to forget the “Indigenous Holocaust” and that it is a paramount episode of American history that the world needs to know about, even for us on our little island of Singapore with our own history of indigenous Orang Asli and the indigenous people of the Malay Peninsula. Given that the world places much emphasis on learning from the mistakes of the Jewish Holocaust and on extending empathy and humanity towards its survivors and their stories, I firmly believe that the “Indigenous Holocaust” deserves our attention as well, and this nonfiction read is an essential book to have for all who seek to be empathetic citizens of the world.

A brief review of “Kill the Indian, Save the Man”

The aforementioned poem by Willie Dunn, an extract taken from the book’s forward, honours the memory of 12-year-old Chanie “Charlie” Wenjack, who died in 1966 while running away from an Indian residential school near Kenora, Ontario, as he was trying to get back to his father and his beloved people.

This book does well to uphold the existence and humanity of its residential school victims first and foremost, and Churchill makes it his priority to highlight their unfathomable struggles throughout ruthlessly displacement from their homes into places of torment and never-ending abuse via the medium of poetry – which appositely captures the sentiment of despair in the loss of contact with one’s loved ones, incapacity in the process of trudging back home and longing for one’s home, family and culture. The anaphoric phrase “Walk on” not only outlines the struggle to push toward reconciliation with one’s culture and home, but it also expresses the determination and resilience of the Native people to persevere through a history of continuous oppression and genocide from a hostile white government.

The book then continues to introduce the notion of genocide within the context of North America, in which Churchill details the types of genocides that ultimately add to the validity and congruence of what constitutes the “Indigenous Holocaust.” These “modes” of genocide include “physical genocide” which involves “direct/immediate extermination,” “biological genocide” which includes “involuntary “sterilisation, compulsory abortion, segregation of the sexes and obstacles to marriage,” and “cultural genocide–which encompasses the schema of denationalisation/imposition of alien national pattern…” (5-6). To not spoil too much information concisely written in this book, I will briefly go through certain pertinent points that Churchill makes throughout his historical and sociological account of the residential school impact.

He then details the processes that involve the “killing” of the Indian in these residential school children, which involves the forceful transfer of children from their homes and families into the residential school system–whereby most schools existed under the Catholic order and imposed the imbuing of the Catholic religion unto indigenous children, thereby forcing these children to relinquish fealty to their former religion and traditions.

He also highlights how the residential school effort effectively imposed the national pattern of the Oppressor, in which the enforcing of a new religion, cultural practice, language, and ways of living effectively force the indigenous individual to denounce their inherent and ethnic worldview and to assume the dominant worldview of the white society. This inadvertently reduces the indigenous worldview to one that is invalid in the modern world, thereby dehumanising the indigenous individual to a lesser being than the white man due to their cultural origins and beliefs.

Churchill goes on to outline a world of pain and inflicted trauma unto the residential school children that is justified in the name of “taming the savage,” whereby these residential schools outrightly disregard the rights and humanity of the children, and it enforces a genocidal intent upon these children by implementing “slow death measures” such as starvation during arbitrary punishments, “indirect killing” by the passing of disease and illness, torture such as waterboarding and caning, and sexual predation by the guardians, nuns and priests at these schools.

I will admit this book is not an easy read due to the heavy and tragic content of the physical and mental abuse of young indigenous children. Yet, I think it is imperative that, as conscious global citizens, we must be aware of histories of tragedy and widespread massacres worldwide, and the “Indigenous Holocaust” is no exception. Given the non-fiction nature of this book, Churchill precisely and concisely profiles the injustices done to the residential school children of North America, and while it won’t be a pleasant reading journey, it will be a meaningful and smooth one because Churchill succeeds in getting right to the point and making his arguments clear in his explanation of the genocidal impact of the American Indian residential schools.

Echoing Gertrude Stein’s “A rose is a rose is a rose,” Churchill calls the residential school episode what it is: A genocide. A massacre. A continued effort to eradicate the “Indian” and all aspects of indigenous culture and self. He does not hedge the details of what happened to these residential schools because he represents the voice of indigenous survivors and communities, who are tired of having their histories and stories twisted and hidden to support the dominant hegemony’s imperative.

Nevertheless, I hope this book opens your eyes to a hidden part of America’s history, and that it will compel you to support and fight against the injustices done unto the marginalised in the world. When I first chanced upon this book, it was the book that propelled me towards a deep interest in Native American literature, history, culture and literary tradition. It changed my life completely, and I hope it will for you too.

Works Cited

“The American Genocide of the Indians—Historical Facts and Real Evidence.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, March 2, 2022. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/2649_665393/202203/t20220302_10647120.html.

Austen, Ian. “’Horrible History’: Mass Grave of Indigenous Children Reported in Canada.” The New York Times. The New York Times, May 28, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/28/world/canada/kamloops-mass-grave-residential-schools.html.

Churchill, Ward. Kill the Indian, Save the Man: The Genocidal Impact of American Indian Residential Schools. San Francisco, CA: City Lights, 2005.

Hanrahan, Laura. “News.” Canada just ranked as the third-kindest country in the world. Daily Hive, November 12, 2021. https://dailyhive.com/vancouver/canada-ranked-third-kindest-country-in-the-world.

Margolin, Malcolm. Deep Hanging out: Wanderings and Wonderment in Native California. Berkeley, CA: Heyday, 2021.

“Native American Cultures.” Native American Cultures | Pomona Museum. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.pomona.edu/museum/collections/native-american-collection/native-american-cultures.

Smith, David Michael. “Counting the Dead: Estimating the Loss of Life in the Indigenous …” Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.se.edu/native-american/wp-content/uploads/sites/49/2019/09/A-NAS-2017-Proceedings-Smith.pdf?bbeml=tp-LoV-wVHX0k6TcA7Wm6g2wQ.jSys0KeQJgUafvsYIdAsKZw.rvHGgn32To02VwLgzvtEx4g.lqjTrZHIjR0WBL7o0wcew3Q.

By: Wendi Lee